Unlocking the Power of Evidence Based Design: Designing People-First Healthcare Facilities

August 8, 2023Post Tagged in

|

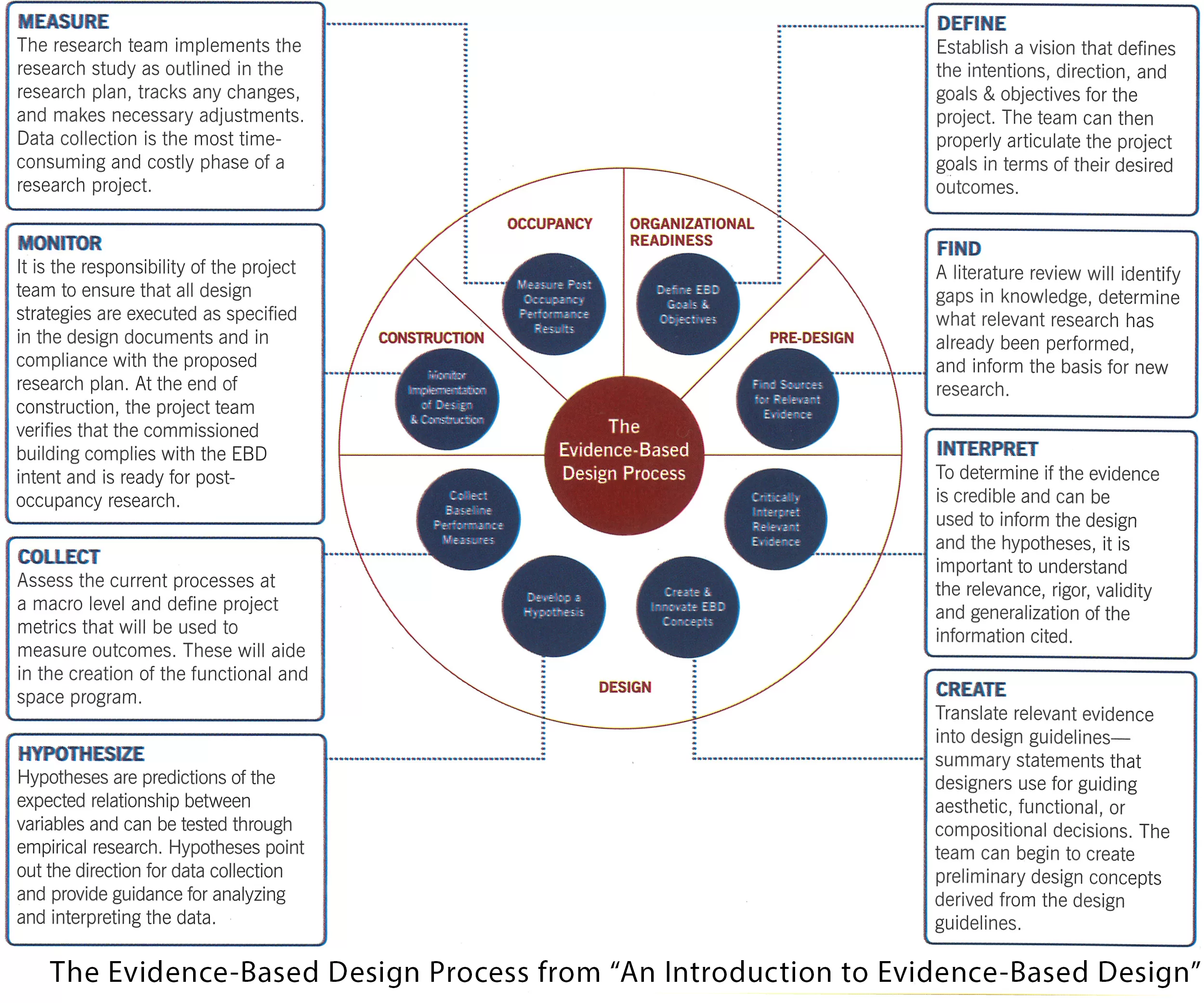

Design Collaborative’s mission to Improve People’s Worlds. We do this by designing People-first Places. But how exactly do we do that? What characteristics of the built environment can actually have a positive effect on the occupants of that environment? And how do we know that what works in one building will have the same effect on occupants in other, similar buildings?

|