Intern Research – Designing to Serve More Than Humans

Written by: Louisa Surtz, Architectural Intern

May 10, 2024Wildlife, both plant and animal, unintentionally find their way into human-created spaces, causing us to question the harsh division we’ve drawn between the built and natural worlds.

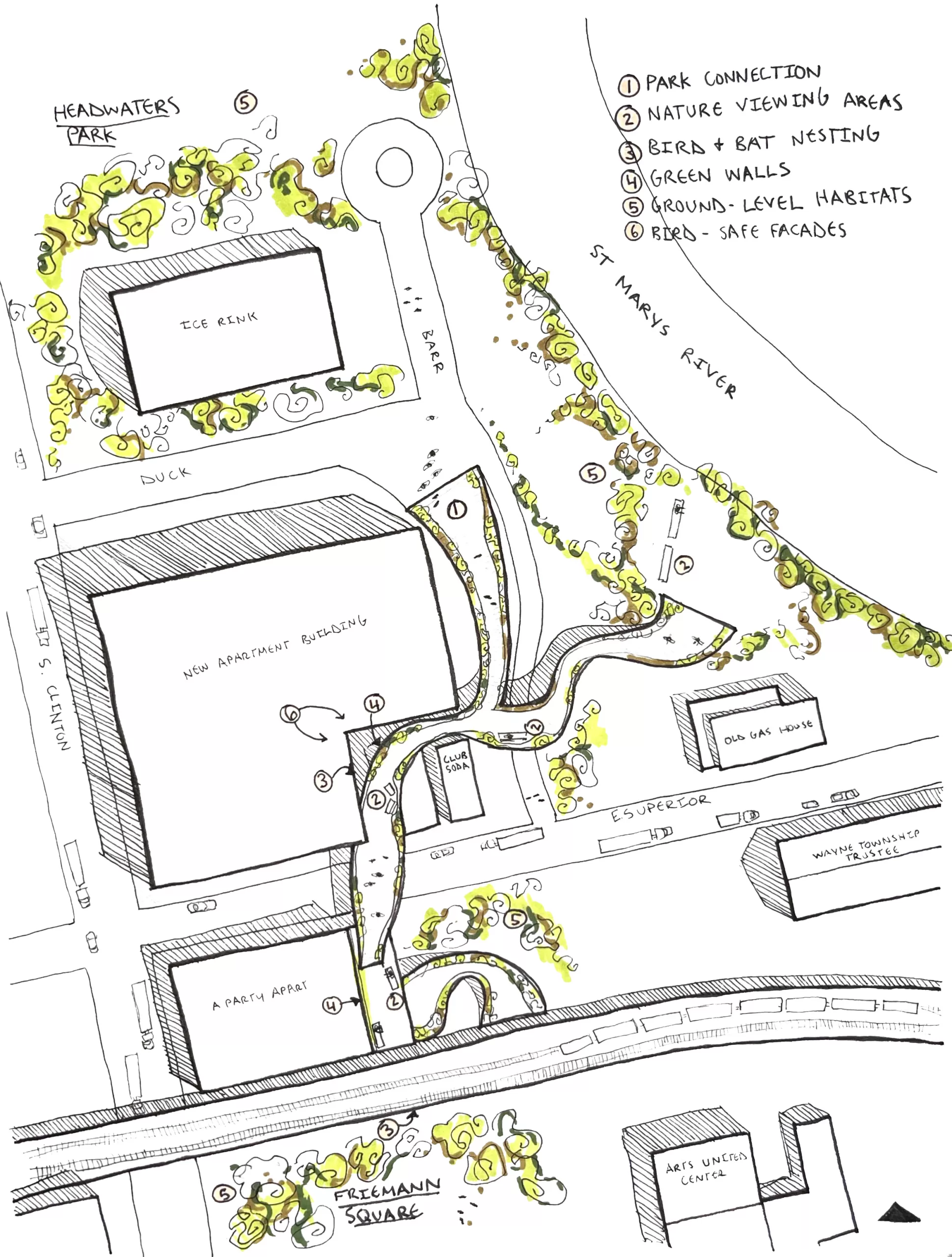

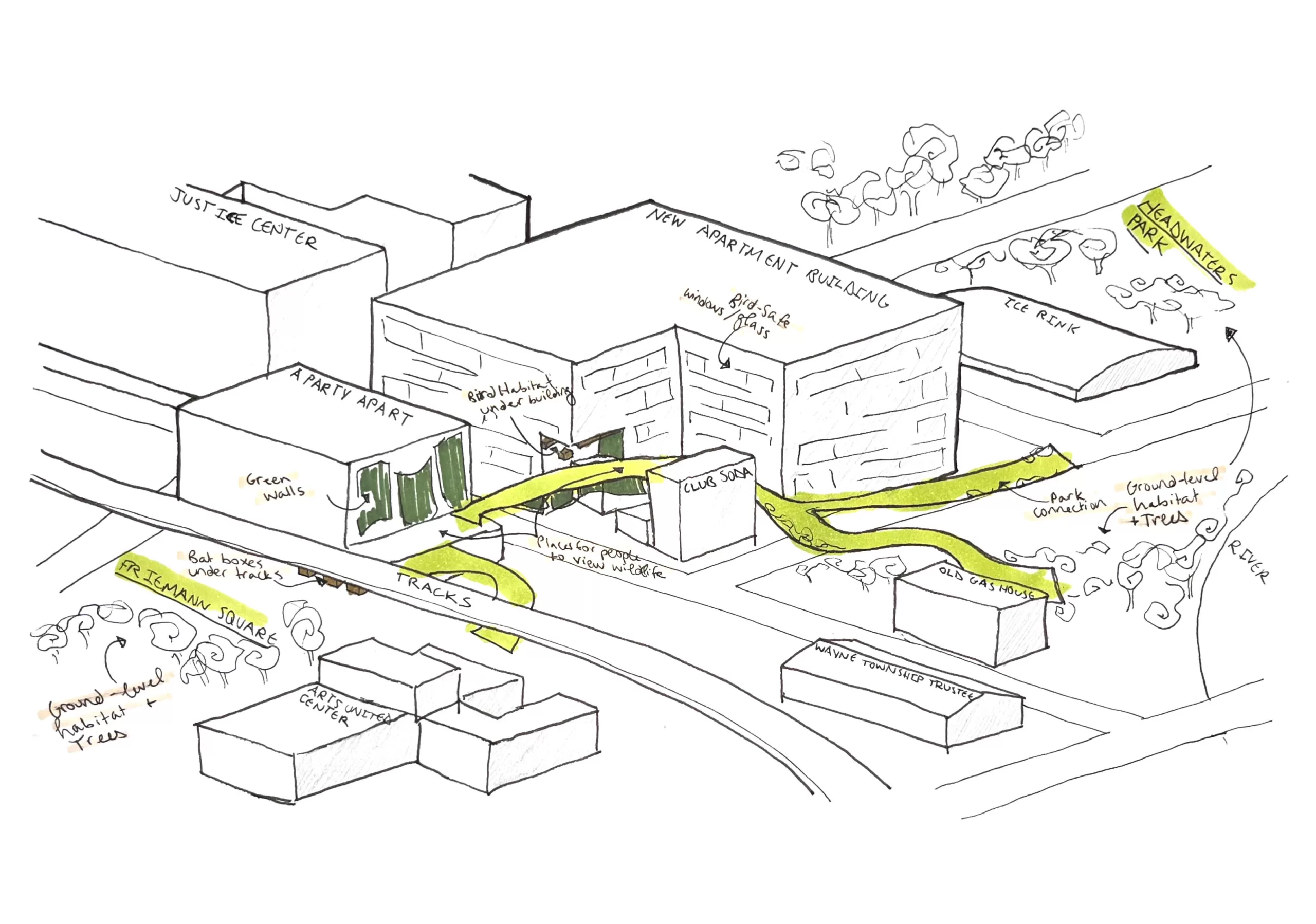

What remedies could be proposed to promote biodiversity within our urban environments? From wildlife corridors to turning an urban area like downtown Fort Wayne into a thriving ecosystem, there are endless ways to imagine a future where cities are designed for the health of both humans and the planet.