Integrating Accessibility

March 7, 2024|

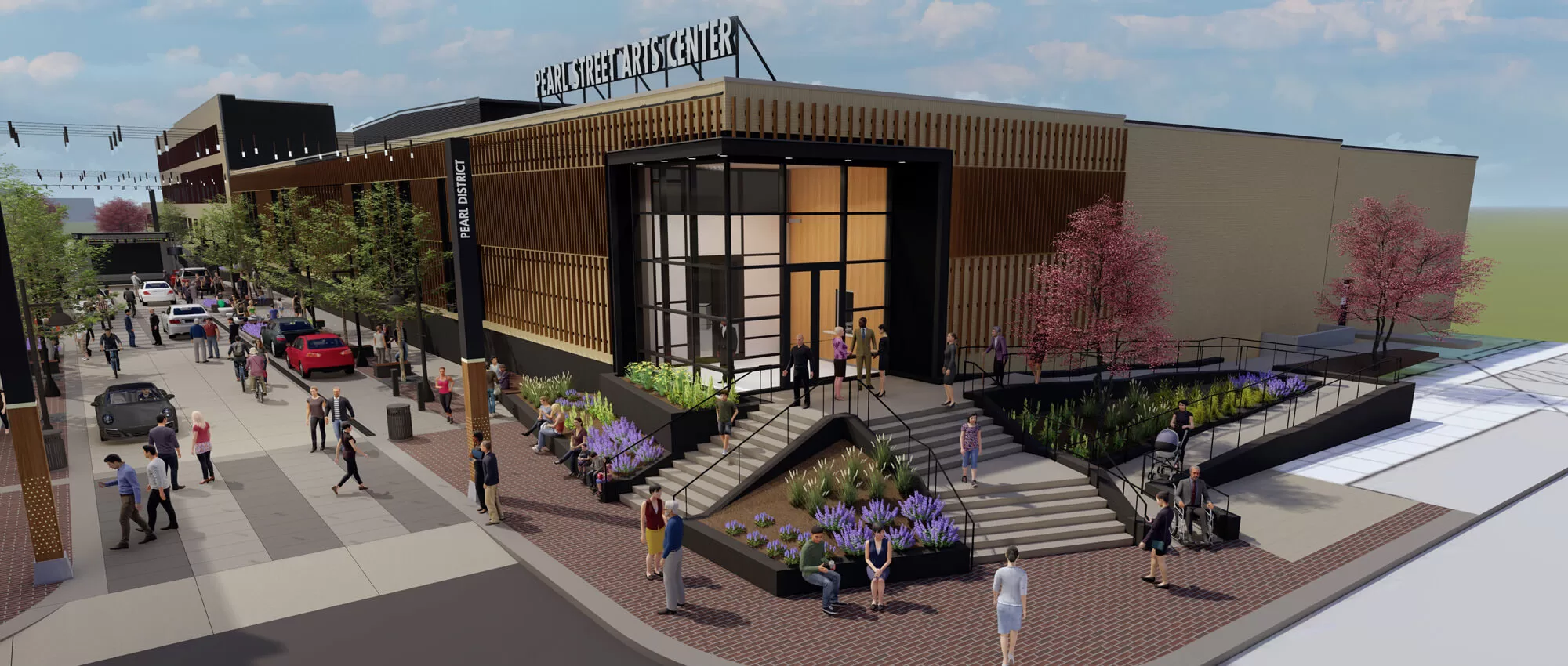

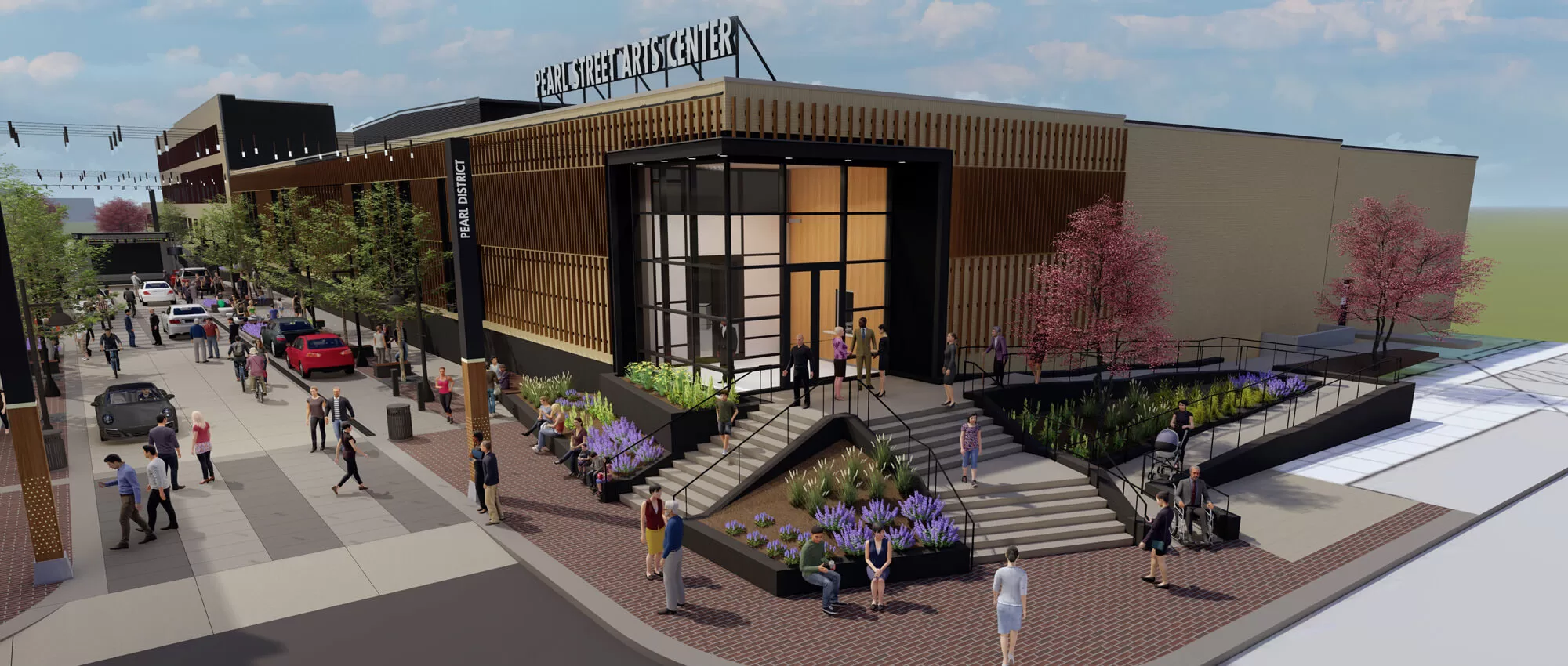

As the executive director of a new arts center being built in downtown Fort Wayne, Jim Palermo wants to make sure it’s accessible to everyone. That’s why he’s working closely with the Design Collaborative team to incorporate universal design into the 37,000-square-foot facility. It starts at the front door, which is six feet above sidewalk level. |

|

|

“We didn’t want the ramps to be too steep, but we also didn’t want to make people in a chair be wheeled 50 feet away and have to come back. We spent close to three months on the main entrance,” says Palermo. “We need to think, ‘How are we going to make that an experience that’s equitable, so that the ramp experience is as good as the stair experience?’” adds Kelly Shields, a senior architectural designer at Design Collaborative.

|

|

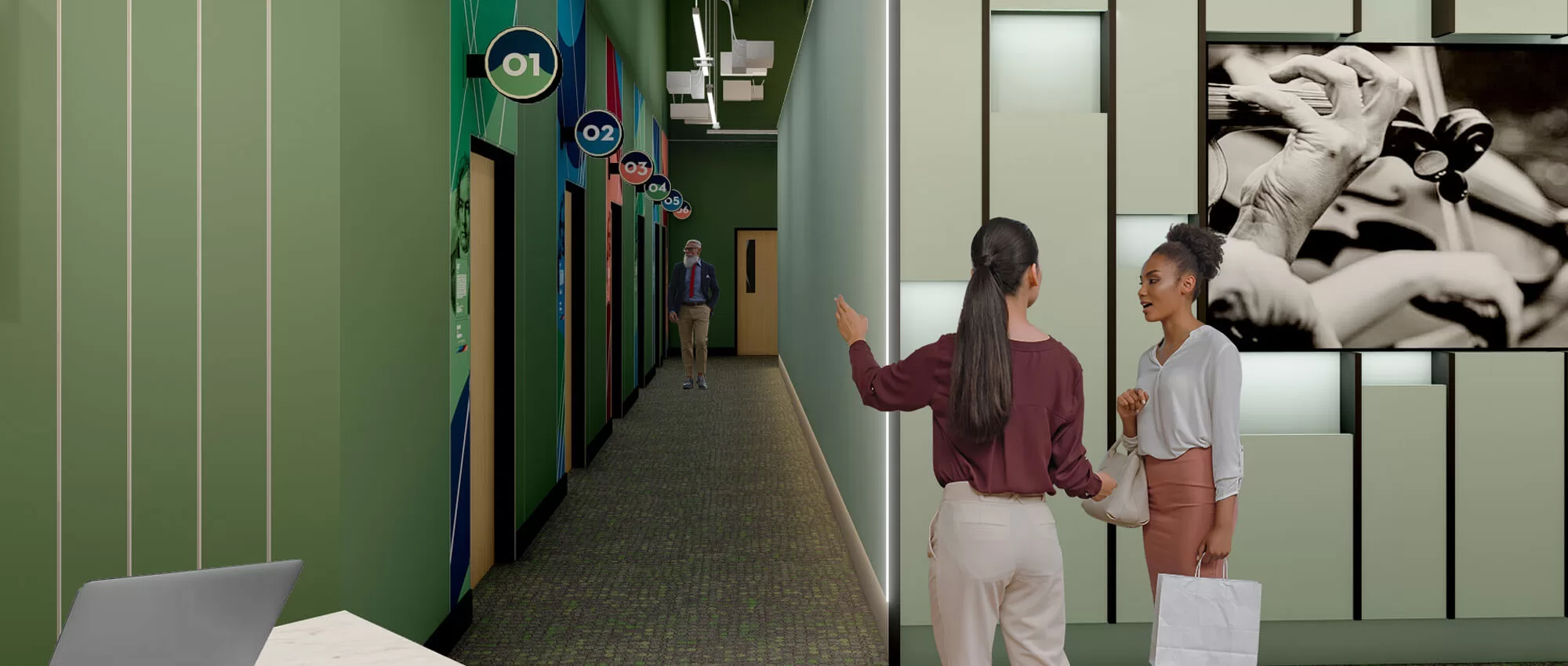

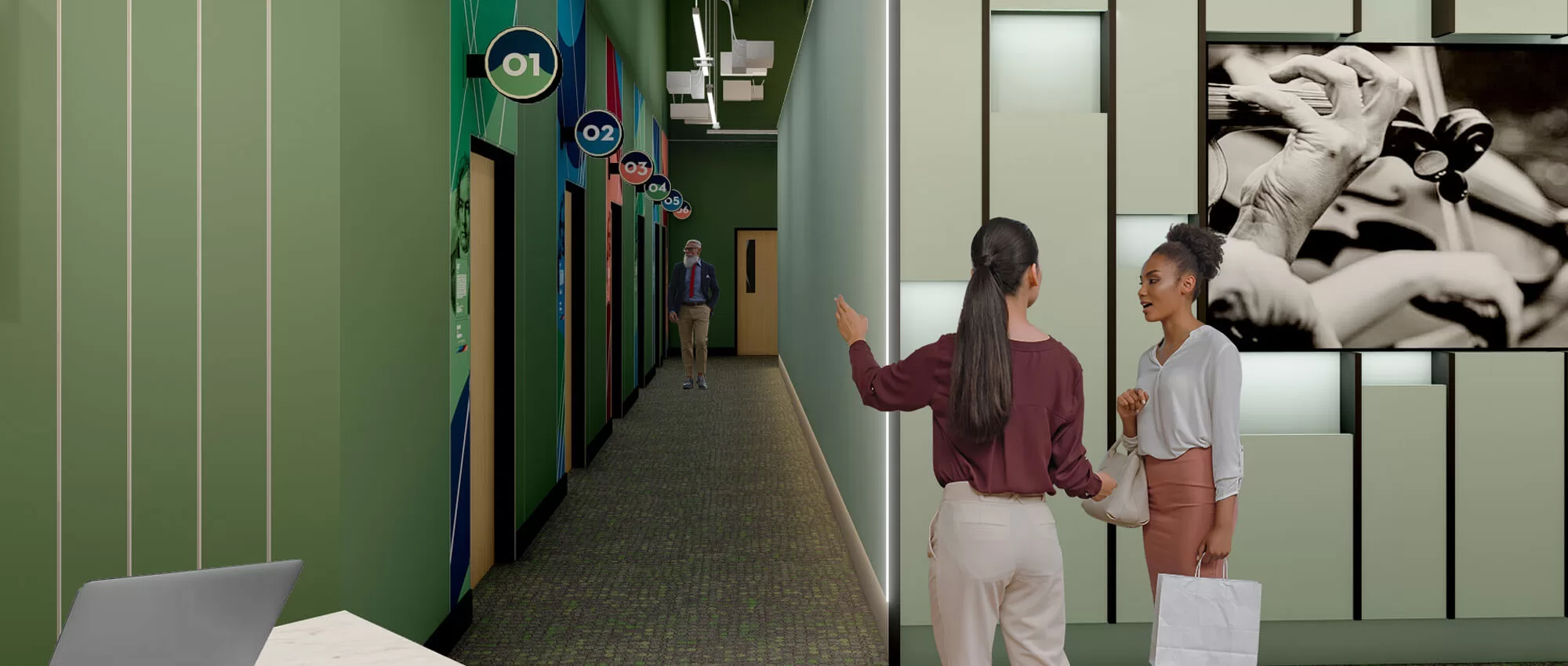

In the past, builders and designers often focused primarily on people with disabilities, but they’ve now shifted to eliminating barriers for every single person in a variety of circumstances. That can range from doorless airport bathrooms that accommodate luggage to touchless entrances for parents with strollers to improved signage or enhanced lighting for people with visual impairments.

|

|

|

“Universal design isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution. We’re realizing that there are common sense things that we can be doing to accommodate a larger group of people,” stresses Design Collaborative Director of Interior Design Lauren Elliott. “It doesn’t have to be overwhelming. For example, there are things you can do with furniture that are really simple; someone might need a larger chair or a taller chair, or door hardware for people who may not have great mobility with their hands.”

|

The Americans with Disabilities Act requires certain accessibility standards, but Shields stresses that builders and designers should strive to not just meet those standards, but exceed them. “We’re always looking to make it better than the minimum,” he says. “We don’t want it to be like an old church that sticks a handicap ramp around back. It’s thinking about adaptation where the ramp is in the front of the building and you’re not necessarily having to find a different path. It’s not just about making sure someone in a wheelchair can simply get into a building. It’s about making sure it’s a good experience and not having them feel as though they’re second-class citizens.”

“It goes beyond thinking about disability and considering things such as how families might be using an environment,” concludes Elliott. “We all vary in shape and size, and our needs are different.”

Article featured in Business People Magazine.